The grandmother: revered

There is something about grandmothers that verges on the folkloric. I recently read this article titled “The Sacred Wisdom of our Abuelas“ and it’s not the first time I’ve heard how a person’s grandma inspires them. My husband and my most recent housemate both speak with deep love and admiration for their grandmothers, particularly the paternal ones.

It occurred to me that there might be a feminist narrative in there somewhere but I stopped myself from overanalysing and decided grandma reverence probably dates back to ancient history. I suppose there’s a genuinely deserved respect and awe for the fact that it was tougher being a woman in that era.

I’m not trying to be dismissive. If it sounds that way, I guess I’m a little sorry I missed out on this kind of experience and connection with my forebears. As a first generation migrant, I didn’t grow up with my grandmothers the way many have. Oh, and in the case of my Ah Poh – my mum’s mum – there was the additional fact of me not speaking her language.

Yet now that she has passed – the last of my blood grandparents – the memories I do have of Ah Poh feel very precious indeed.

Random (yet sacred) memories

I remember her sitting at her dresser, its triptych mirror panels hazy with age, the wooden stool with its misshapen red vinyl cushion. Or maybe I just remember the dresser? It was mysterious and a bit magical, full of small items foreign to me because Mum never wore make-up. I remember the curved porcelain that sat beside the little alarm clock in the bedhead shelf – Mum said they were Chinese pillows. I couldn’t believe anyone could be comfortable, let alone sleep, on one of those.

I remember how she used to feed stray cats at the soy sauce factory. She’d yell out a high-pitched miew miew, upon which a dozen or so of the straggly things would flock to her. The factory was a place with a particular pungence – dark and relatively cool within the high-ceilinged warehouse, glaring and hot without. After my grandfather’s death, she took up the reins in the manager’s office, wielding a black abacus instead of a calculator. No computer in sight. Meanwhile, baked brown under the tropical sun, wiry half-naked men toiled over cauldrons of fermenting soy beans. I loved that she was such a bosswoman.

I remember her non-stop stream of mostly random chatter, her tell-it-like-it-is good humour. The way she fussed over my mother and bantered with my father.

I remember when we went out shopping or for a meal, how she used to stuff wads of grubby cash into her bra to keep it safe from pickpockets.

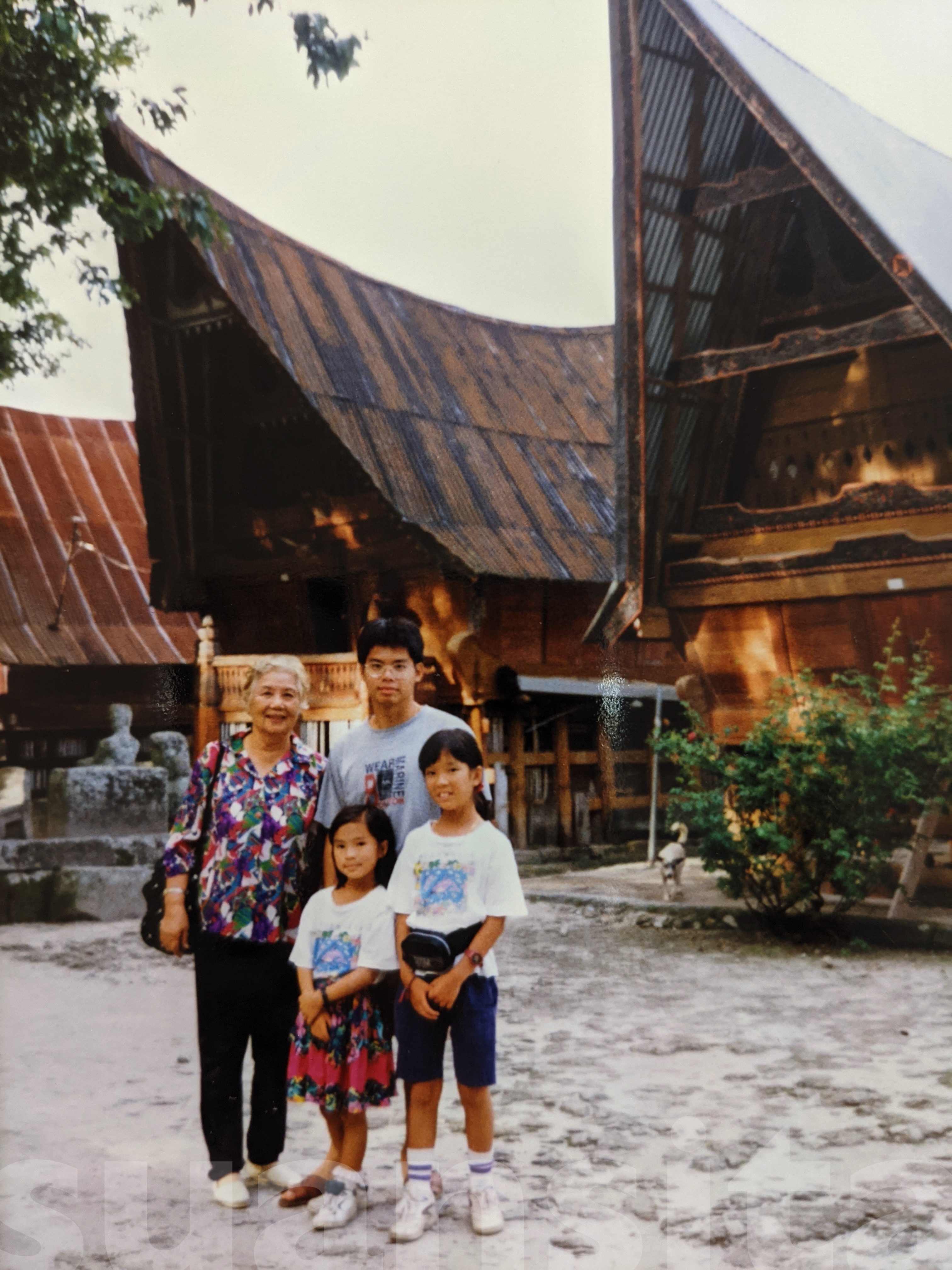

I remember her gloriously patterned pantsuits. I wish I had pictures but I do not. I do, however, have some pictures of her in a colourful shirt (below left) and characteristic nighties (below right).

I remember the time she sent my parents back to Australia with a gift of two inappropriately lacy pairs of underwear for me. The panties were seriously ugly but the absurdity of receiving a gift like this from one’s grandmother gave me a laugh and endeared her more to me.

I remember in each of these vignettes just how strikingly unlike my own mother she was.

Ah Poh with my infant mother. Loving the classic cheong sam!

Ah Poh holding newborn me.

Random (or sacred?) advice

One of the last things she said to me, the last time I saw her in Kuala Lumpur in October 2015, was a piece of advice offered over herbal soup at the dining table.

“Stop volunteering and get married,” she said, rather offhandedly. As was sadly often the case in our exchanges, I understood fragments (the bit about marriage) but my mum had to translate the rest.

At that point, I had just wrapped up a year volunteering in Bolivia. In the next few years, I settled into paid employment in Sydney while she had to be moved to a nursing home.

I don’t know if she knew I was getting married this year. Coronavirus swept across the country and the world, came upon that nursing home. She was infected the day I walked down the aisle, transferred to a hospital ward shortly after.

For a while, it looked like she would recover and in fact, they were about to discharge her from hospital when she breathed her last. She was 97.

I wish I could have seen her one last time, that she could have met my husband, my niece. I draw a little comfort in seeing that, sacred or not, there must have been some grandmotherly wisdom in her last piece of advice. After all, I did end up following it.

RIP Chue Lai Peng, b. Guangzhou, 13 November 1923, d. Kuala Lumpur, 20 July 2021.

4 comments

Thanks Hsu Ann for the lovely essay on grandma. You’ll be happy to know that she knew you were married. I have been speaking to her, telling her of your wedding plans and even about your sister and Amelia, & others and my last conversation was on your wedding day (just after you marriage). She was very happy. I wasn’t aware she had covid then. She sounded her normal self. Happy and very alert (reminiscing about things. She had better memory than myself). I miss her sorely.

Thank you for sharing your random & sacred moments of your Ah Poh. I so relate to this strange form of intimacy we have with distant grandparents and feel privileged to share a small piece of your experience with it.

Oh so well said, “strange form of intimacy with distant grandparents” – that’s exactly what it is! Thanks for reading and sharing how it connected with you??