I am one of those sad souls who spent far too long at university with little to show for it. After six-and-a-half years, I finally collected my undergraduate degrees. For the next six-and-a-half years, I honestly couldn’t stomach the idea of returning to do a masters, let alone a PhD. It’s silly, isn’t it, having such a strong reaction to university. It’s as if I’ve somehow been traumatised by my education. This aversion to academia is, I think, borne out of a disappointment with my experience of undergraduate law and arts (humanities, or liberal arts).

The more I think about it, however, the more I see that this disappointment wasn’t limited to my formal education. I also became increasingly uneasy with what I was seeing in church. My experience with academia turned out to parallel my feelings towards the evangelicalism I grew up with.[1]

The following reflections are based on my unique experience of academia and of evangelicalism. I’m using academia and tertiary education as shorthand for the law and humanities subjects I took, and evangelicalism to describe the narrow range of church traditions I’ve been exposed to. I’m conscious others may have had radically different experiences of university and of church.

So with that disclaimer, allow me to share with you what drew me to formal education and to religion, how they both disappointed me, and where that leaves me now.

Attraction

One of the things I loved most about school – and which university offered to an even greater degree – was a holistic and logical approach to understanding the world. There wasn’t much ROTE learning in my education (which I’m grateful for), but there was a strong emphasis on process, and on critical thinking and self expression within a certain structure. Here are some examples:

- Frameworks for essay writing: introduction, three arguments, conclusion

- HIRAC structure for law assignments: heading, issue, rule, application, conclusion

- We were encouraged to develop our own opinion, but required to support it with primary and secondary sources, and citing those

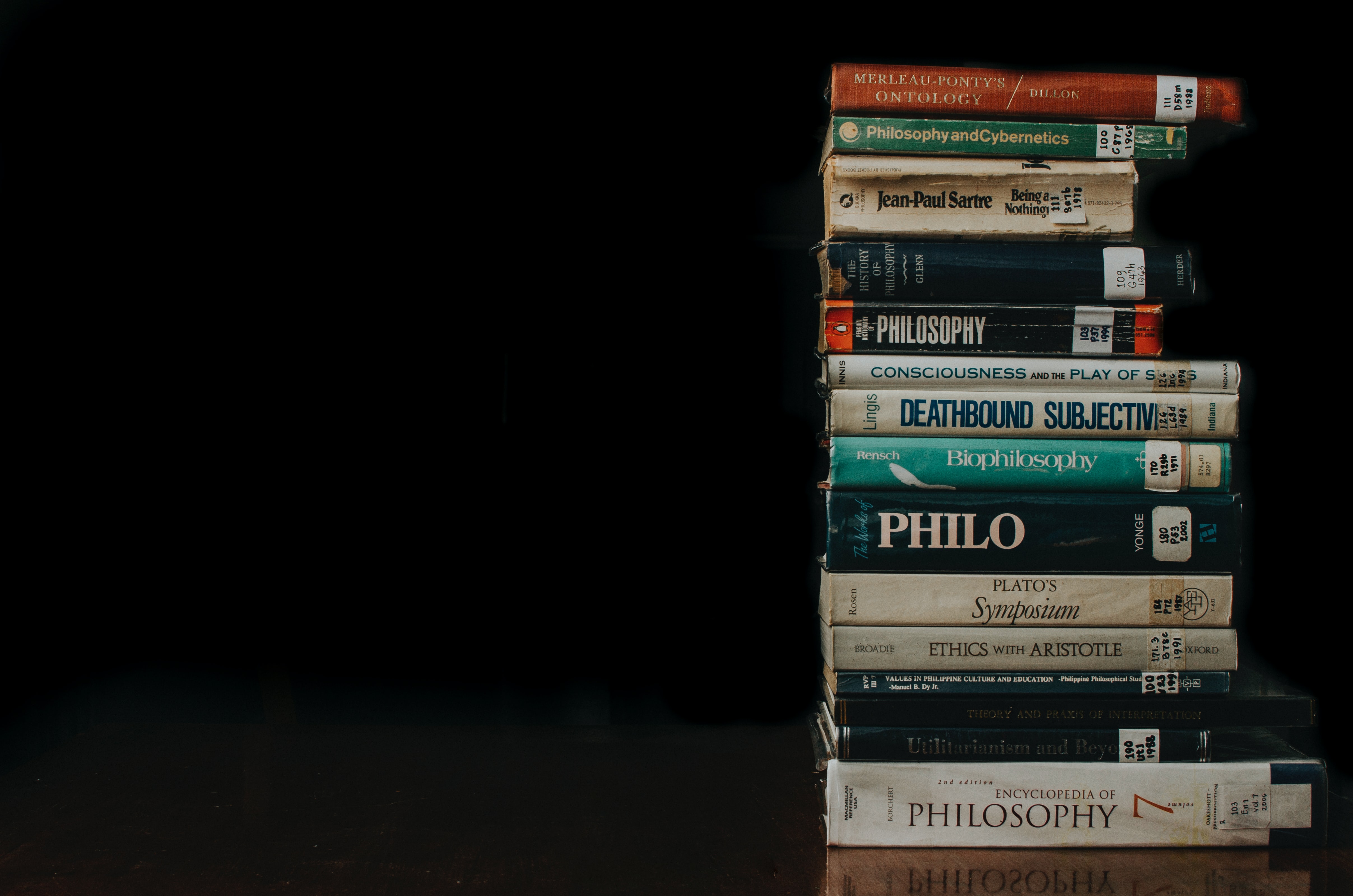

Three-point essays with thorough referencing were drilled into me from high school through to uni. I loved essays. I loved the ideas that we talked about in literature, philosophy, history and politics classes: interpretation, themes, narratives, metanarratives! I really loved synthesising ideas.

Likewise in church, the central activity at our weekly youth group was studying Scripture. There were frameworks for this too, such as the Swedish method and SOAP: Scripture, Observation, Application, Prayer. Discussion was always anchored in what you could read in the text of the Bible.

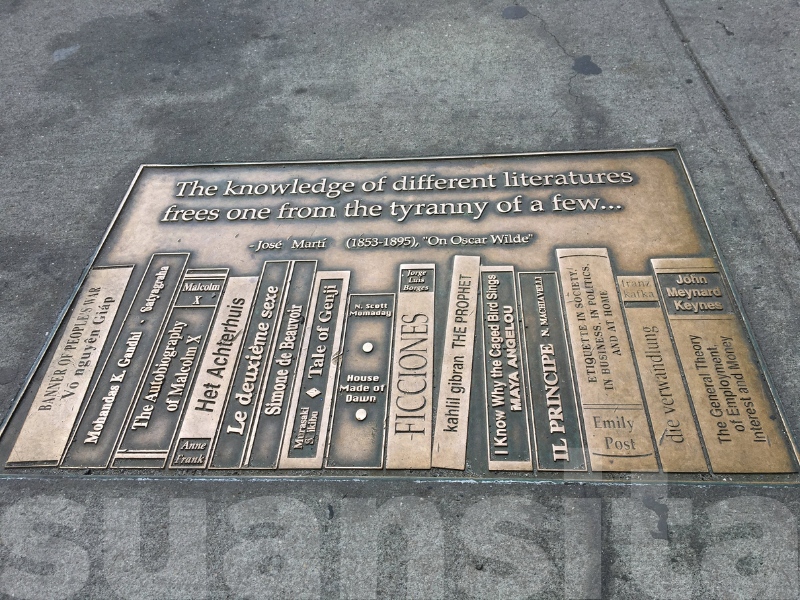

Later, lunchtime Bible talks run by a Christian group at uni were incredibly nourishing to my spiritual growth. All that exegesis and unpacking of Hebrew and Greek words cast new light on familiar verses, demonstrating an ingenuity and depth to Christianity I hadn’t previously appreciated. It felt like a light-bulb moment of revelation seeing how Jesus was the focal point for past and future. Seeing how all of the Old Testament pointed to Him cast life and the universe in a whole new light. Christianity made sense. It had a historical basis and a logic I could follow.

In this regard, academia and evangelicalism are very alike. A three-point sermon is to the standard evangelical church service what a three-point essay is to secondary and higher education. Tracing every element of our beliefs and practice to a book, chapter and verse of the Bible parallels tertiary education’s citation requirements. There’s a clear formula: open with a relatable, ideally humorous, personal anecdote before setting out the three main interconnected ideas you’ll draw out of today’s Bible passage, then close by tying it all back to Jesus on the cross (if, in fact, the entire sermon was not already about Jesus on the cross). It reflects, essentially, an academic approach to Scripture and to religion.

Disillusion

But alas the shine began to fade. I became disillusioned with the way both academia and evangelicalism focused on theory over practicalities. I started to get the sense that neither of them were as clever as they thought they were. Neither had an adequate response to the brokenness I saw in the world around me.

The longer I spent studying the humanities, analysing and arguing grand theories about human nature and our society, the more I felt a disconnect with that world and the one I actually lived in. All my history, politics, development studies and law courses were extremely negative about humankind and the future of the world. They criticised everything (calling it “critique”) yet offered no alternatives, no hope.[2] What was the point of a neat structure and clever ideas if they didn’t help make the world a better place?

Meanwhile my faith came to a point of crisis not with a cataclysmic life event but with taking courses in medieval philosophy and the philosophy of religion. I started to not only see, but feel, the limits of Reason in proving the existence of God or anything meaningful about my relationship with Him. I began to question things I had been taught about the Bible and what it means to be a Christian.

The neat formula of three-point sermons felt insufficient in the face of life’s messiness. Doctrine and rules seemed incompatible with a personal relationship with God. If anything, they seemed to put the theoretical mechanics of individual salvation above actually interacting with God, or taking concrete steps to transform our own and others’ lives.

I found this particularly frustrating because justice had been, and continues to be, a driving theme in my own faith journey. While I don’t believe the purpose of faith or the Church is to fix all the world’s problems, following Jesus necessarily involves attending to the needs of the people around us, both near and far. Yet for all the Bible’s talk about loving our neighbour, many evangelical traditions consider justice – alongside politics, culture and worship music style – to be secondary to Scripture. I’m convinced this is a false distinction, that charity and justice are part and parcel of the gospel of Jesus: both a logical outworking of being in relationship with Jesus and a way in which we show people Jesus is, indeed, good news.

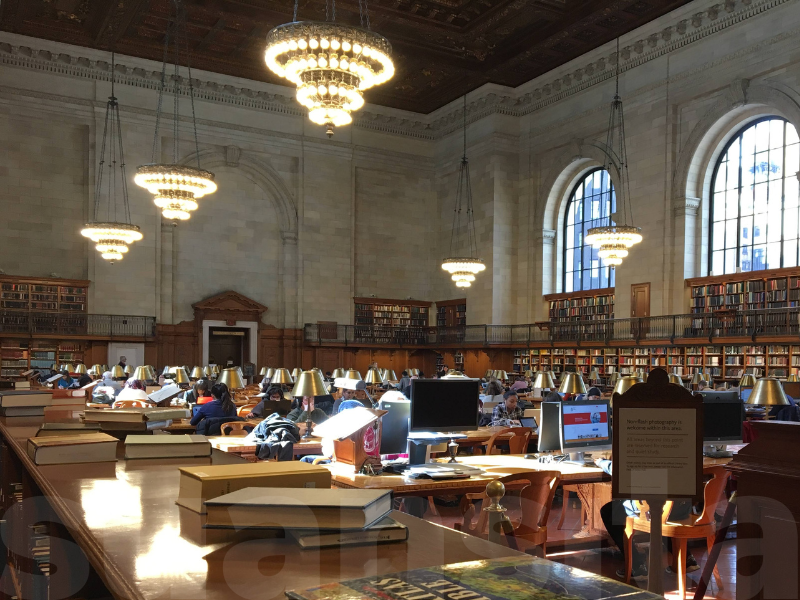

Perhaps the problem is not that theory is bad but that contemporary evangelical churches are too much like universities with lectures (sermons) and tutorials (Bible studies). The current church model is geared towards keeping congregants within the institution (as undergrads, then masters, PhD then postdoc students) rather than preparing them for the workforce or mission field. There is a place in society for academics, but not everyone in society should work in schools and universities. The body of Christ is more than a higher education institution. Surely it’s family and community and so much more besides.

Tension

Despite my disenchantment with evangelicalism, it wasn’t enough to undo my faith. For all the things I questioned, one thing I couldn’t shake was a certainty that God loved me and Jesus was (and is) who He said He was.

And let’s be real: I’m still drawn to essays, literature, history and all the metanarratives that come with those. I’m simply mindful of their limits and their pretensions. Academia and academic approaches to faith have provided a strong foundation for me. In a way, they’ve given me the freedom to think beyond those frameworks and ask these questions.

Where does that leave me then? Right now, rather than asserting or debating anything, I prefer to present our faith as more beautiful, more mysterious, yet simultaneously authentic, more real and relatable. I prefer to try my best to embody what I believe, even if I’ll inevitably fall short of the mark.

This hunger to go beyond academic approaches to life and faith has helped me embrace things like creativity and more mystical spirituality. These in turn have given me a certain freedom and joy, and a sense of growth. I feel like I have been able to more fully inhabit myself, and more intimately experience God.

Both my progressive public education and my conservative evangelical church experiences shaped the person I am today, probably in more ways than I can put my finger on.[3] Facing my objections, while conscious of my debt, to these two forces in my life is a little uncomfortable. Like growing up and becoming aware of the things I’d do differently from my parents: I love them and owe everything to them but disagree with some of their approaches to life.

To be frank with you, this post has taken a year to write because I struggled to get it right. It was too tempting for me to pigeonhole a particular denomination, to infuse this piece with my own resentment, to skew it with my own judgment. It was difficult to get to the point where rather than criticising a particular expression of the Christian faith, I am able to fairly and accurately show you how my secular and religious education were similar in their approach, how that blessed me and frustrated me, and how seeing the limits of that approach has fuelled my personal growth.

I hope that it has blessed you to read about my journey. Please feel free to share your thoughts with me.

[1] It’s interesting that my entire education has tended progressive while the evangelical Christianity I’ve been exposed to tends conservative, so this isn’t really a matter of politics for me.

[2] Something I have identified more recently is that I dislike apologetics. That sums up a certain posture or attitude that I find distasteful in both academia and evangelicalism.

[3] This is evident in the structure of this blog post – that irony is not lost on me.

4 comments

Like, pido permiso para compartirlo con mis jóvenes

Claro que si! Gracias por leer y espero que mis palabras puedan animar a tus jóvenes?

Excellent post! I love how a sense of disquiet in both contexts has given you freedom to think and explore beyond more common frameworks. I love how this continues to draw you into the passionate pursuit of justice and a deep desire to be a shield for those who are vulnerable.

Thanks Dave, grateful as always for your encouragement?