Early inspiration

I suppose that every writer, whether professional or amateur, has work from their past that they’re seriously embarrassed to have brought into the world. One example in particular comes to mind. I wrote stories all through my childhood and adolescence and am generally proud of what I penned, but I did have woeful phase in Year 10 where I mimicked the style and tone of the Apostle Paul’s epistles.

I shudder to recall this. Perhaps one day I shall transcribe and publish these writings for your viewing pleasure. Perhaps I shall destroy them.

Paul’s writing was key to my early understandings of faith. His letter to the Romans was an eye-opener for me as a teenager – it showed me what the Old Testament had to do with the New Testament and just why Jesus was so special and so necessary. Even now, I find him articulate and compelling as a writer, and admire that he unwaveringly lived what he preached.

And yet, I do feel a sense of unease when I come to those much-maligned passages on women keeping silent (the fact that there is context to explain those references doesn’t stop them from feeling like a slap in the face). When certain evangelicals cite his lines to “prove” that women should not be allowed to preach.

In short, many evangelicals love him and many atheists love to hate him. And many Christian women, like myself, feel some really complex and conflicting things about him and his teaching.

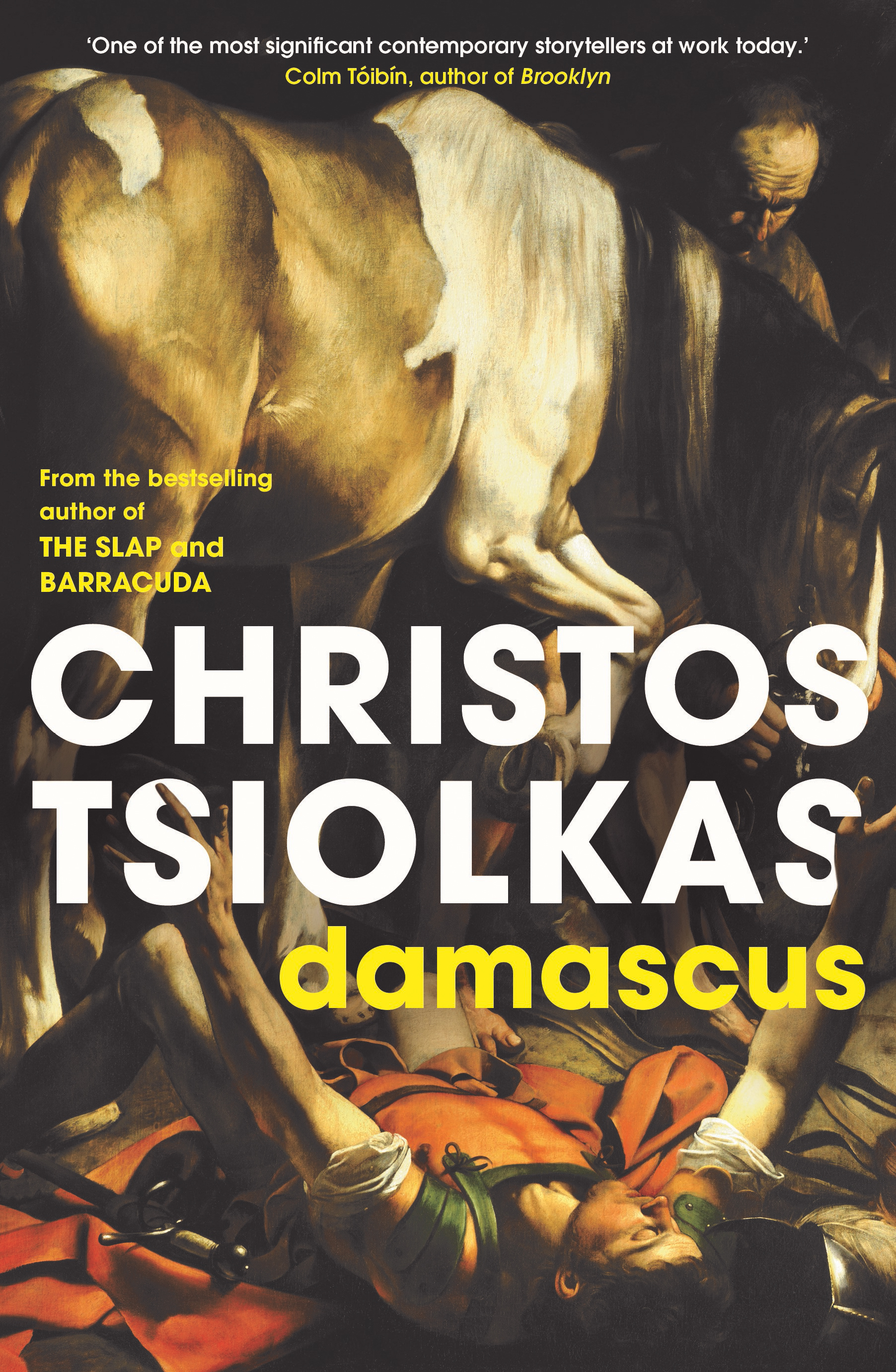

Damascus

When I heard about a new work of historical fiction about the life of Paul, my curiosity was piqued by the fact that it was written by a non-Christian Australian writer and positively reviewed by two Christian reviewers.* Anne Lim opens her review by saying she “had to peep through parted fingers shielding my eyes” as she read because of the sheer brutality depicted in this book.

My experience was similar. I flinched and winced my way through the audiobook, read to great dramatic effect by Saul Reichlin. Despite the excellent, evocative reading (or perhaps because of it), the book was a real slog – I almost didn’t survive the whole way.

- Photo credit: Hassan Almasi.

It is graphic. It is brutal. It is full of violence and lust – which after all, are not dissimilar things.

While I haven’t read The Slap or Barracuda, Tsiolkas is known for being a provocative writer who is unafraid and unflinching in delving headfirst into sensitive, often taboo, topics.

Having now experienced Damascus, I come to the conclusion that this is a really important book for Christians and non-Christians alike, precisely because of how graphic and brutal it is.

Paul’s humanity

I feel that as a Christian, I have been painted a particular picture of Paul. Although I have read his letters many times over the last 18 years and can see both passion and compassion in his writing, my portrait of Paul has been somewhat sanitised by contemporary preaching on the theological concepts in his work.

Paul has been pitched as the model follower of Jesus. He saw Jesus even though he wasn’t one of the original 12 disciples. He had a superior understanding of Jewish Scripture and who Jesus is. He endured way more tribulation than we ever will yet rejoiced in his suffering rather than complaining like the rest of us do.

What is lost in this rendering of Paul – that we get in bucketfuls in Damascus – is his raw humanity. While Tsiolkas’s reimagining of Paul as a repressed gay man may or may not be factual, he reveals to us a Paul who is deeply human. His Paul struggles constantly, with lust, jealousy, insecurity, doubt, rage, pettiness and the list goes on.

We can read in the Bible Paul’s own words about his weakness:

But somehow we tend to focus on then I am strong. Why do we do this? In so doing, we gloss over what it meant for Paul to be weak. We don’t ask ourselves how exactly he was weak, whether his weaknesses may have been akin to any of our own. Perhaps we’re in too much of a rush seeking a soundbyte of advice on how to be strong. And when we do this, we disempower Paul, his message and ourselves.

Non-Christian critics of Paul can also tend to overlook his humanity. He gets such a bad rap, particularly in conversations about Christianity and sexuality and/or gender, but this book reminds us that Paul was a real person with real struggles – and real valour. Tsiolkas is generously compassionate towards his complex, flawed Paul character and amidst the uncomfortable vices that plague him, we see how his genuine love and leadership transform the lives of others around him.

It is this deep humanity, encompassing both the most depraved of vices and the noblest of virtues, that makes Paul’s role in establishing the early Christian Church and shaping the faith confessed by over a billion people today, so remarkable.

Rome’s brutality

The devotion of Paul and other early Christians – including Timothy, Lydia, Thomas and James featured in this book – is all the more remarkable because of the brutality of the times they lived in. We may have a picture of Roman cruelty in the form of the Arena (I mean, who hasn’t seen Gladiator?), but Damascus reveals how the violence was everywhere, all the time.

Whether it’s the exposure of female babies, the lack of hygiene leading to disease or the painful rituals demanded by Roman gods, the violence was unrelenting. We totally miss that when we picture flowing togas and eloquent Roman senators.

We think it’s radical that the early disciples sold their possessions so they could share all things. That’s more extreme than communism! we say. Damascus reminds us even the simple concept of having one God outside of Creation, or communing with slaves, was so scandalous as to be unthinkable in the first century.

Contemporary society thinks of Christianity as archaic, patriarchal, institutionalised and representative of the status quo. Yet it actually began as a counter-cultural movement of men and women. Who knows, maybe now as the West becomes increasingly postmodern, we can revive this spirit of counter-cultural courage.

*

Christians and non-Christians alike have overlooked what it means for Paul to be a flawed human in a vicious, unforgiving world. Damascus gives us that.

I could do my best to shake off a sense of reverence, untouchability, about both Paul and Scripture itself to reimagine early Christians in new, non-canonical ways. But I suspect it would be a leap too far to drive my imagination into the depths of depravity within the human soul and society to create characters like these, a world like this one.

Tsiolkas has done this. He’s done a phenomenal job of this. And he has nonetheless managed, masterfully, to retain a real respect for his characters and what they stood for.

The book is nasty yet beautiful. Even as I flinched and winced my way through it, I could feel my appreciation of and compassion for Paul growing. I could feel my gratefulness growing for Jesus and how he turned the world upside down.

Despite the obvious liberties taken in inventing characters and their relationships and the use of some unbiblical theology (particularly in relation to Thomas), there is a lot of important truth in this book. I’d encourage you to take a deep breath and dive into Damascus. The humanity and brutality depicted is confronting, but it might just help develop your empathy and respect for your fellow humans – and yourself.

The two reviews of Damascus I read were:

- “‘This world is not enough’: Christos Tsiolkas’s radical remembering of the Christian revolution” by Simon Smart – for helpful discussion on some of the historical and theological elements in the book that I have only briefly touched on.

- “Why Christos Tsiolkas is keen to talk to Christians” by Anne Lim – for an interesting look at the author’s process in writing the book and his own feelings about Paul and Christianity.

Header image: Luca Lago.

2 comments

Good review Ann.